Deconstructing Deconstructions

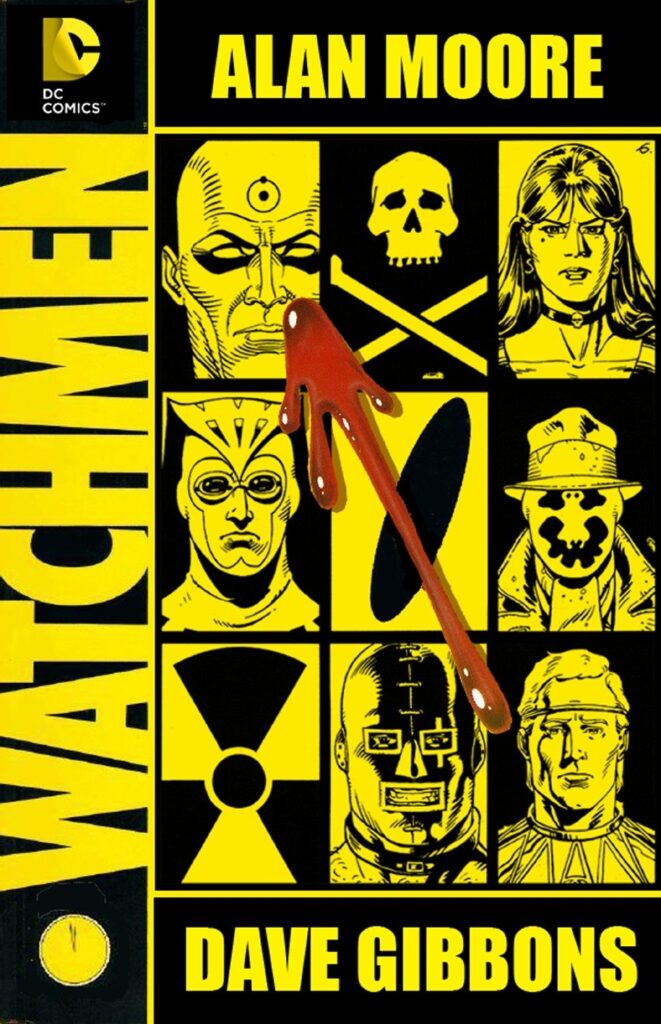

I am somewhere in the middle of my third readthrough of Watchmen, Alan Moore’s most popular graphic novel (which still falls short in comparison, to my mind, to his V for Vendetta). Now, I am an Alan Moore fanboy. I think he has done things with the medium of Graphic Novels, or I’ll just say it out loud, comic books, that were not deemed possible until he rolled along. He pushed the medium forward from superhero romps to a medium that could tell layered, nuances and incredibly complex stories. He of course stands on the backs of the giants that came before him, but that does not take away from how far he saw on his own.

One of the classic defining features of Moore is his disdain for the idea of superheroes. Everything from The Boys to Injustice: Gods Among Us, can trace their origins on a straight line to Moore’s works. Even if you read these works distanced from their inspiration, there is a very clear difference in how they approach their subject matter. The Boys, more concerned with the shock value of the immoral and disgusting things superheroes can do, never really questions the idea of them. It merely harps on the age old idea of “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” This is the key difference between Moore’s work and all that follows. Moore deconstructs, while others merely imagine how these ideas would fit into the world we know and live in.

They might seem similar but there is a world of difference between the two. A critique takes a thing and tries to understand it against a backdrop of multiple things, its own origins, the prevailing narratives in society and often, the critic’s own morality. Deconstruction attempts nothing of the sort. Instead, it takes an idea, breaks it apart and then studies them on their own, distanced from the fixations of the critics. It is like writing a review for a car versus taking the engine apart. Deconstruction takes more time but has deeper insights waiting for you at the bottom of it.

Take Watchmen for instance. What makes it different from the million other series that followed which had assholes dressed up as superheroes? It is breaking apart the idea of a superhero itself. In the story, there is a metanarrative of sorts that is set-up, tracing the evolution of superhero themselves. Watchmen begins with masked adventurers, and follows them until they reach the final crescendo of the God like creature, Dr. Manhattan. This is similar to how superheroes evolved in comic books as well. Superman in Action Comics #15 could only leap over tall building. Now, he punches suns into blackholes every third issue. This escalation of powers, a common but lazy way to make readers keep coming back for more, was understood and played on by Moore. So where is the deconstruction here?

Before, we must answer that, we must understand the prerequisites to deconstruction and why so many fail at it. Before anything else, deconstructing a thing requires an intimate knowledge, possibly even a reverence, of the thing. Moore, a life long comic fan, had put in his 10,000 hours studying the medium before he started working in the industry. This knowledge, collected painstakingly and without any expectation or reason, is what makes him so well suited to deconstruct the genre. The way he deconstructs the superhero trope shows in his work as well. He is aware of what makes for a good superhero story, and then dissects them further to find the pearl at the centre.

If you study Watchmen, the parallels are there for you to see. We have Superman, Batman, Wonderwoman (in some fashion in Silk Spectre), even Punisher, all of them present in the story. But what Moore does so brilliantly, because he has taken the engine apart, is swap parts. He strips the superpowers away from Wonder Woman and focus on the titillation of the character. He takes Superman, a character whose defining trait is his humanity, and rips it apart, leaving behind the cold indifference of Dr. Manhattan. He takes Batman, his gadgets and plans, but rips away the drive and obsession that makes him tick, leaving behind the pathetic mess that is Nite Owl. What is left at the end is a series of characters we all know and love, but feels like we are seeing their reflection in a funhouse mirror, distorted, grotesque and somehow perversely funny.

This I believe lies at the heart of deconstruction and what makes it distinct from criticism. Criticism does not bother to fiddle with the parts, only wants to comment on them. Deconstruction takes matters in its own hands, swapping out bits and pieces, like a jigsaw puzzle, until the pieces all fit, but the puzzle does not resemble the original picture on the box anymore.

I feel this is the purpose artists like Moore serve in society. They demonstrate how we can question what we have always known and possibly loved. I am reminded of a quote from Angels and Demons (I think) where Nuclear Physics is characterised as boorish, because it is akin to throwing a clock out a window to the pavement below, just so you can see the parts inside. There is inherent violence in deconstruction. You take ideas that you are comfortable with, notions that you have grown up with and therefore consider sacred (of course Superheroes are supposed to be the good guys) and then hack away at them, mercilessly, no parts are sacred. Once the idea you recognize so well has been dismembered beyond recognition, you try to piece them back together, like a twisted game Dr. Frankenstein would play. Some parts would not fit as well you would have liked, so you go grave robbing the cemetery that is the library and dig up bodies (of work) that would supply you with new parts that might fit.

At the end of it all, of course, lies a monster. Coherent, intelligent, brimming with humanity, but ultimately, grotesque to the untrained and uninitiated eye.

Leave a Reply