Jalti Chattan by Gulshan Nanda – A Retrospective

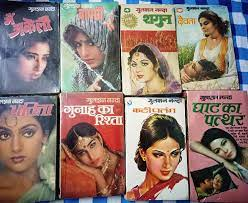

They may be too modest to admit it, but any time a writer gets into the profession, they always have dreams of being immortalized for their work. Now, in many cases, those dreams remain that. Dreams. For a vast variety of reasons, either their works do not get noticed, or they don’t find acceptance in the market, immortality eludes them. However, the writer I will be talking about today, did not suffer those problems. At the height of his popularity, the first edition of his books sold five lakh copies. He himself waas nominated for the Filmfare award for Best Story 6 times in a career spanning roughly 20 years. Yet, if I walk up to the average person on the street today and ask them if they knew who Gulshan Nanda is, I would in all probability draw a blank stare.

Now, to be fair, just like almost all my generation, I had no idea who Gulshan Nanda was either. I was introduced to him by my father, who used to read him in his college days. My mother clearly did not approve, but we will address that later. As I hit the second half of my 20s, and started writing more seriously, I went deeper into reading more Hindi Literature. I had polished off much of Premchand, but that was the extent of my knowledge about literature in my own mother tongue. So when my father mentioned names like Dharamvir Bharti, Gulshan Nanda and the sorts, I jumped in headfirst.

Jalti Chattan is a romance novel written by Gulshan Nanda. I wish I could tell you the exact year it was published, but despite searching for a good twenty minutes, I could not find it anywhere (in our zeal to protect the purity of our language, we destroyed some parts of our culture more thoroughly than others, but I get ahead of myself). We can, for the time being, assume it is set sometime in the 60s, mostly because that was the time when Nanda was writing regularly. It follows the story of Rajan and Parvati. Rajan is a worker in a coal mine, a big city boy moving to a small hill town to get away from the busy life of Calcutta (yes, Calcutta. Kolkata wouldn’t be a thing for decades to come). Parvati, is a pious, quick witted orphan girl who lives with her grandfather. Boy meets girl, they fall in love (in a rather nice, and then another rather creepy meet cute). But then, girl’s grandfather is informed of their relationship by a Iago like character, he dies of a heart attack and marries Parvati off to Rajan’s manager. Standard Bollywood melodrama from the sixties follows. You can clearly see the screenwriter Nanda in the works of the novelist Nanda. He sets up action set pieces, there are songs inbuilt into the narrative so they don’t feel jarring in the eventual adaptation and there is pretty heightened dialogue, lots of “Show, don’t tell” executed rather well.

Coming to the story, I found many similarities to the more literary “Gunaho Ka Devta” by Dharamveer Bharati. It’s a similar tragedy of star crossed lovers, separated by caste and class. The woman is expected to sacrifice herself for some random higher purpose, mostly God but sometimes society as well. Someone dies of heartbreak by the end. Plotwise they are very similar, but “Gunaho ka Devta” is more expansive. So my recommendation would depend on your tastes, If you like literary fiction, Dharamveer Bharti is your guy. If you want a competently written, but shorter and a cuter read, Nanda is where you should go.

Now, coming to what I have been dying to talk about. The Eradication of Nanda is one of the most surprising things I have ever seen. It is equivalent to readers not knowing who James Hadley Chase is. In his space and time, Nanda was not any less relevant than a Chase or a Chandler. But 50 years later, hardly anyone knows who he is. Not just that, many of his books are out of print and even lost now. Yet, he is the same person who was essentially a rainmaker. He gave Rajesh Khanna his first big breakout role in Kati Patang (1971). He went on to write many epochal films in Hindi cinema, like Sharmelee, Daag and Ajnabee. And yet, today barely anyone working outside the industry of films remembers him.

Now, this would have been understood if he had just been a screenwriter. Prior to Salim Javed, writers in films were an afterthought, working for peanuts and often for no credits. Given how Nanda did his most influential work before Salim-Javed burst into the scene, it would have been inexcusable but understandable. However, that is not the case with Nanda. He was an immensely popular novelist of his time as well. Yet, his legacy as a writer has mostly been forgotten if not intentionally erased. And for that, I place the entire blame on the Hindi Literati.

Look, let’s face it. Hindi literature is suffering. Sales have been down for decades. Many iconic magazines and periodicals have shut shop. I challenge you to name three writers who have published anything in the last three years. Chances are you can’t, because at some level Hindi writing has turned into writing for other writers instead of for readers, and the scene is suffering because of that. And for a scene in such doldrums, the arrogance of dismissing literature that is liked and loved simply due to its classification as “Pulp”, is simply shooting yourself in the foot.

There is a common adage, “One for the kitchen, one for the soul”. Many great artists follow this and for good reason. We need to understand that “Avant Garde”, the movement that pushes art forward is called so for a reason. It is because it does things that the normal audience is unfamiliar with. Popular literature exists within the boundaries of what is familiar and comfortable and that is not a bad thing. No battle is won just with an advance guard, you need the foot soldiers and the strength in numbers behind you. A lasting regret in Nanda’s life had always been that he was never considered at par with the “serious” writers, despite outselling all of them put together. I think that is failure of us as a culture that we allowed it to happen.

My mother, who reads often and extensively, thumbs her nose at the pulp literature. She belongs to the time when anything that mentioned sex was deemed as a lesser form of literature. Be it the crime thrillers of Surendra Mohan Pathak or the romance novels of Nanda or Ranu. I feel it is our responsibility as the next generation to undo that and assign credit where it is due.

Until we do that, we will be stuck pretending to be deeper than we are and be much shallower as a people for it.

Leave a Reply